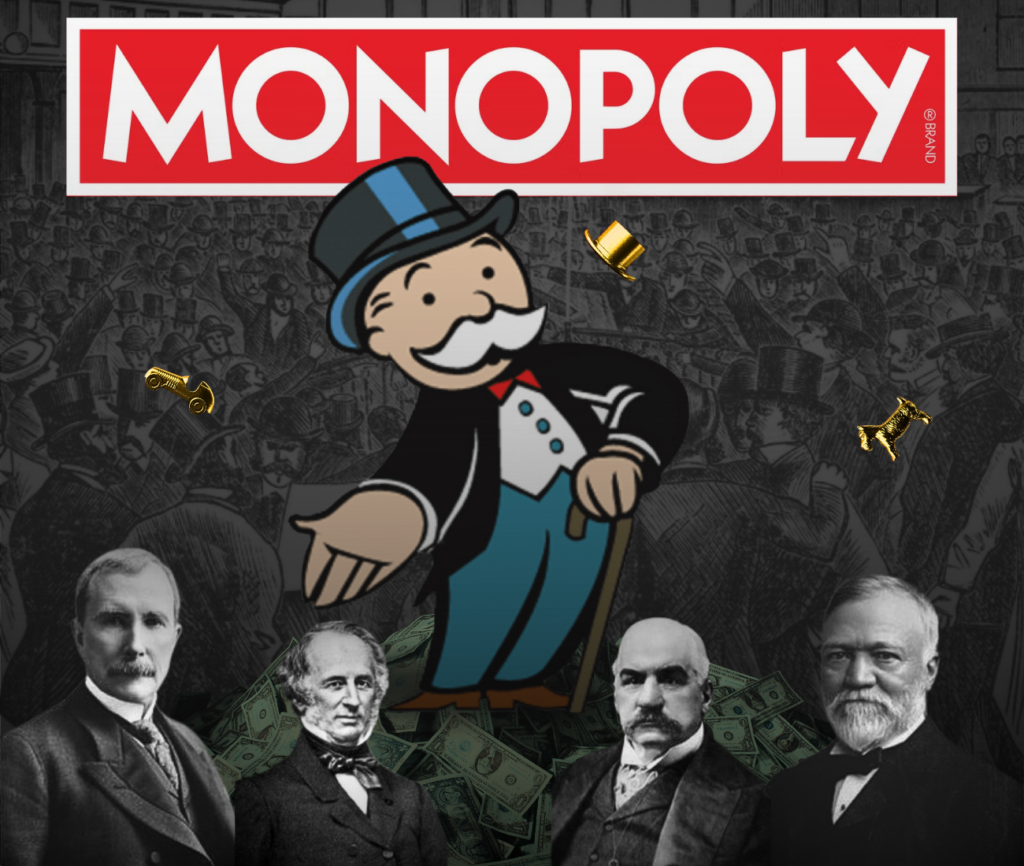

Look closely… Beneath the bright mustache and beaming smile of Mr. Monopoly lies a greedy truth that has profoundly scarred America.

Once a game that reminded Americans of the Robber Barons’ dominance, it is now the eight-and-up dinner board game. Long ago, big figures such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and J.P. Morgan ruled America under the oil, steel, railroad, and even finance industries. These seemingly pleasant fellows who surged during the Industrial Era in America each owned monopolies that employed ruthless tactics, such as bribery and worker exploitation, to amass immense wealth, creating vast inequality and corruption—and, in the end, only driving prices higher.

As the symbolism has now faded, so has the spite of monopolies. Either the average American has degenerated—or the government shows a blind eye toward monopolies (maybe both)… but who cares? We get great shipping from Amazon, good devices from Apple, and excellent platforms to connect with friends on Facebook!

If we look closely at Monopoly, we can identify its key components: houses, hotels, properties, banking, and jail. Since two dice determine the player’s movements, properties that are oriented seventh in rotations are the most popular for players to land on (two dice tend to roll a total of seven). Core institutions like jail make it even more likely for players to land on housing directly seven after jail, so when players are presented with a market of residential houses, some houses will offer a higher return due to their positioning. Though not a direct feature of the game—in reality—landlords have much more freedom when pricing houses if they own more houses in an area—for the client has no other options when visiting the location. The game makes up for this by doubling prices when the house set is owned by one landlord, and only then can they buy houses for the property. Each house explicitly increases rent income, so the player must manage the risk of buying more houses or holding money for the unexpected Boardwalk hotel (very expensive!).

Just like real estate, it is important to know the value of the assets you own—or want to own, so when properties are up for auction, you never pay more for locations that will not prove worthwhile in the grand scheme: dominance. This is also an important aspect of the core mechanic—trading—and while you do want to scam your little sister in the exchange of properties, you don’t want to lose your fortune to your clever uncle. Every player values each house differently, so when trading with a player who undervalues a house, you always want to appeal to their liking in order to obtain properties at less cost. The reciprocal can be stated for players who overvalue properties—you have to realize the potential power that a property holds in order to sell for more.

“The best time to expand is when no one else dares to take risks.”

—Andrew Carnegie Tweet

Quoted above is the key to Monopoly—or at least monopolies years ago. Andrew Carnegie prizes risk-taking as the skill required for power—and in the Monopoly world, the same can be said. The further the player travels down the winding road, the greater the risk of sudden ruin. The general pricing for housing along the track rises progressively. Although it might feel comfortable developing penthouse suites on Baltic Avenue, there is only so much pricing potential in trade for speedy construction. At the polar opposite, Boardwalk is much more risky to develop—but in return, any unlucky businessmen who stumble into even the premises will be incinerated with the rent fees. Keep in mind that developing houses on Boardwalk will also be much more expensive than other properties, so it is up to the player to decide whether they want a steady or an instant gamble at monopolization. Everything depends on the current circumstance; if your opponent is prepared for the long game, you might as well quickly renovate the cheaper properties to cripple him in a scrimmage.

It might feel like you were destined to become the next real estate tycoon after a few games of Monopoly, but it doesn’t take that much scrutiny to realize that the game may fail to capture certain aspects of how the world really works. Now relevant, Blackstone, an established private equity firm, has effectively started its own Monopoly game—branching within the New York district. After slipping under the radar, it now faces strong headwinds as the city has imposed rent control to prioritize tenant rights. People don’t like skyrocketing rent costs—now not with pitchforks, but people are ready to overthrow a disliked regime. New York is a prime example of the current push for housing affordability, and state representatives voice their concerns thoroughly. These residents are afraid that rent prices will leap even more, while they value cheap essentials over newly constructed luxuries. Blackstone would never have expected its assets to fight back, but with other currencies vacillating, perhaps the NYC tenants are just the complacent type. Who knows? With so many funds to store, you could become a mobile piggy bank for Blackstone.

Maybe America isn’t prepared for the approaching real estate monopolies, but considering the current state of companies, we recall the true purpose of this game. With a hazy familiarity, we realize that we have fallen into the trenches of another monopolized era—maybe for the best or maybe for the deserved attention.